The great resignation: everyone's talking about it, but why is nobody embracing the elephant in the room?

it’s time to address the roots of the issue.

Columnists from the Guardian, Financial Times, Daily Telegraph, as well as LinkedIn bloggers and workforce experts, have all had a crack at answering why we have one of the biggest phenomena in voluntary and structural unemployment in 20 years: why do so many in the UK want to leave their job in the next year?

Some of the predictable answers you will have heard are: poor middle management, not enough holidays, improving employee benefits, and at worst, that people need to just ‘get on with it’ and find a job, whatever that might be.

All of these concessions remind me of why I could never work for a company without a four-day work week. And although, save for the lattermost reason, these are relevant symptoms to discuss, it’s laughable how far from the bullseye the arrow’s landing, when we currently stand no further than a meter from the target.

This deliberate cognitive dissonance has been addressed by many; the likes of David Graeber in his book Bullshit Jobs, James Suzman in Affluence Without Abundance, Franco 'Bifo' Berardi in his book Futurability: The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility, even John Maynard Keynes’ monumental economic theories.

They all agree on a similar thing: in the future, with incredible advances in technology (which is now), we can and need to work less.

I'm going describe what the elephant in the room looks like and feels like for me, and why adopting a 4-day work week as the standard is less radical and absurd than sticking to the current 5-day doctrine of work.

Berardi argues that…

"technology enables the enhancement of social experience, and that particularly makes it possible to work less and enjoy more. But as soon as it is transliterated into economic terms, technology fuels frantic hyperactivity and competition on the one hand, and unemployment on the other"

Berardi is telling us that we need to let technology make our lives better, not just in terms of how we spend time outside of work, but how much time we have outside of work.

It’s easy to see this when we consider how increasing pressures on our finances, ‘hustle’ cultures of overwork, and the increasing difficulty in finding work that feels meaningful, paired with needing to work to survive, have had a palpable negative effect on people’s mental health.

In a poll conducted in the UK in 2020 by Personnel Today, it was found that "work-related stress is the most common form of stress in the UK – one poll found that only 1 percent of employees had never experienced it – while 1.6 million workers are suffering more generally from work-related ill health”.

Where for me, I assure you without irreverence, sleeping in on a Friday morning is a reality I thoroughly cherish. Having a cup of coffee by the windowsill and deciding whether my day will consist of kicking it with the homies, or maybe I’ll work on some music? Or maybe there’s more immediate household chores to get out of the way, much ado about it all.

Importantly, I decide. Sure, in the world we live in today these aren’t cure-alls. You might choose to do something different with your Friday, and I hope you do. Personally, having an extra day in the week to myself has done wonders for my stress levels, health, and happiness.

However, we can see with the UK’s 6-month 4-day work week trial, as well as how similar trials have been reported in the past, the primary indicators for their success are upshots in productivity and falls in absenteeism.

As more of us reclaim our Fridays, the success of 4-day work weeks will increasingly hinge on our wellbeing and happiness instead. And given that it’s probably not a leap for me to say you care about your happiness and wellbeing, and that it’s definitely not a leap for me to say I care about yours, why not start that conversation now?

But to make sure you’ll actually be better off and happier for it, a great deal of attention needs to be paid to maintaining a four-day work week. This isn’t just about putting it into company policy and sending a company-wide email. It needs contingency planning and a thorough change in the culture of an organisation and its members.

Especially if you’re a younger member of the workforce, fresh out of high school or university, with few connections to grant you security, competition between young workers is rife. The job you worked hard to earn is unfortunately a job that you know you’re easy to replace in.

That competitive survival mentality is a hard one to defeat. Of course, even for us we occasionally need to work a few hours on a Friday, though that is importantly an exception to the rule- however, if everyone thought they could get a leg up by working on Friday, the four-day week would no longer exist. The same is true for any company.

Another important topic when considering the relationship between work and mental health is the fulfilment we gain from work.

There’s a nation-wide, at times unspoken expectation that everyone should aspire to be fulfilled by their salaried work, and that anything beyond that must be confined to a hobby or become unmanageable.

This is why we talk about better work benefits like free gym memberships, more training opportunities, mental health support, better middle management, and more holiday, rather than addressing the more fundamental root of the problem; how much time we spend at work, and what that time looks like.

Speaking to people from all walks of life with a plethora of different interests and stories, figuring out a beautifully simple and compelling strategic plan, contributing to visually and emotionally striking creative campaigns, nailing that debrief and getting into an invigorating chat with a client, are just some of the things I find fulfilling about working as a strategist.

However, I also gain a huge deal of fulfilment from writing, recording, producing and performing music.

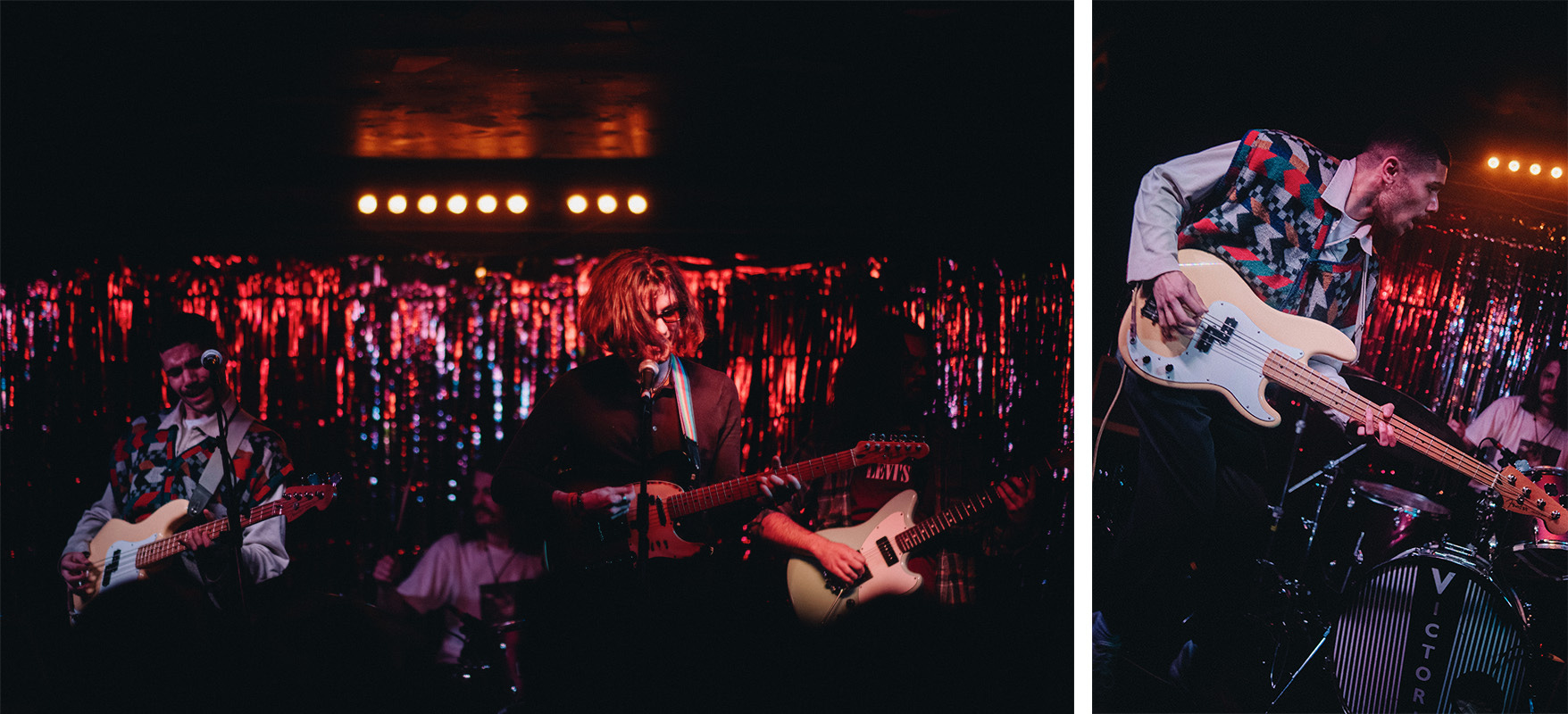

The feeling of chaos and euphoria when the strobe lights slice everything you see performing on stage into freeze frames of joy. The feeling of getting together with my friends and writing music we all get excited by and believe in.

These are things that require time, energy and planning, and things that traditional 5-day working weeks can’t accommodate comfortably.

James Suzman’s research tells us that during the pandemic, furloughed workers in the UK, “found work to do, but that work was much more satisfying than their jobs” (Vice, 2022). Switching to a 4-day week, as I’ve experienced personally, permits people to also pursue meaning and fulfilment outside of work, which puts less pressure on the workplace to provide this.

Allowing for this to be the case ultimately not only leads to a happier and more fulfilled workforce, but also to a workforce with more diverse thinking, and a greater breadth of experience to draw from.

Of course, these changes to the way we organise work and how much time we spend at work cannot happen in isolation. If working less is the way to tackle the “great resignation”, government support in the form of policies like Universal Basic Income, rolling out greater automation, and increased support for businesses in making these transitions will be necessary.

It is infinitely more absurd to stick to a 5-day work week, than to begin a conversation with your friends and colleagues about moving to 4 days instead. Given the points above, it’s fair to say the future can be hopeful and full of greater joy and fulfilment for everyone involved. The great resignation has little to do with the symptoms of how we work at this stage; it’s time to address the roots of the issue.